Guest post by Janine Barchas

Today puts another candle on the birthday cake of novelist Jane Austen, born 16 December 1775. Conveniently, Austen’s birthday coincides with the December gift-giving season. If you are thinking about making a holiday present of a Jane Austen novel to that budding (or confirmed) Janeite in your circle, you are spoiled for choice. In conjunction with the 200th anniversary of the original publication of Pride and Prejudice, this calendar year has witnessed a mushrooming of both new and newly repackaged Austen editions in a wide range of binding styles and price points.

In your choice of edition and inscription you may, however, want to reflect upon the long-standing history of the Jane Austen “gift book.” Whereas this year Jane Austen novels in both hardcover and paperback formats have been aggressively prettified in the stalwart fight against the e-book, these same stories have long been a gift-giving choice for everyone from aunts and uncles to schools and churches—even hotels and soap manufacturers. Not all of these uses of Austen as prizes and giveaways are duly recorded by book history.

|

|

| Jane Austen as reward for good hygiene in 1890s

Soap manufacturer Lever Brothers published editions of Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice during the 1890s as part of a unique marketing campaign for Sunlight soap. The first English company to combine massive product giveaways with large-scale advertising, Lever Brothers offered a range of prizes in “Sunlight Soap Monthly Competitions” to “young folks” (contestants could not be older than seventeen) who sent in the largest number of soap wrappers. The Sunlight advertising blitz was targeted to working- and lower-middle-class consumers, and proved such a boon to sales that Lever Brothers ran the competition for a full seven years, annually escalating the giveaways. Prizes included cash, bicycles, silver key chains, gold watches, and—for the largest number of winners—cloth-bound books. For this purpose, Lever Brothers published and distributed its own selection of fiction titles by “Popular Authors” and “Standard Authors,” including cloth-bound editions of Jane Austen’s works. By 1897, the year the competition closed, Lever Brothers had awarded well over a million volumes. |

|

|

|

| Jane Austen as church and school attendance prizes in 1910s

Pretty but inexpensive gift books had begun to comprise a familiar genre by the end of the nineteenth century. Middlebrow publishers like Ward, Lock, and Co. of London promoted the hundred-plus titles in their “Lily Series,” which included all of Austen’s novels, as “gift books at eighteen pence each.” The same title could be purchased in different colored cloths, so as to better tailor its look for the intended recipient. Gift books also came with various options that ranged in price: “Very attractively bound in cloth, with design in gold and silver, price 1s. 6d.; also in cloth gilt, bevelled boards, gilt edges, 2s .; or ornamental wrapper, 1s .” With or without gilt and bevels, such books were deemed particularly suitable as “admirable Volumes for School Prizes and Presents to Young Ladies.” These two copies of Northanger Abbey were part of “Blackie’s Crown Library Series,” published circa 1910. Both were awarded as attendance prizes and survive with their original pasted certificates: one was made out to “Winnie Valentine” in 1916 by the vicar of a Sunday school in Yorkshire, and the other is addressed to “Annie Munro” as an “attendance prize” in 1911 from the School Board of Forfar, Scotland. From an additional inscription in a child’s hand on the flyleaf, it looks as if Annie eventually re-gifted her prize to young “Florence Munro” (or at least allowed her to claim possession). |

|

|

|

|

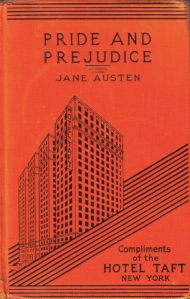

Hotel Swag, or Gideon Jane, circa 1930 In the 1930s, the largest hotel in Times Square had custom editions of Pride and Prejudice strikingly bound in bright orange with their building’s façade on the front cover, to offer to guests as giveaways. Inside the complimentary copy, patrons of the Hotel Taft found the full text of Austen’s novel as well as an advertisement for the salt water pool at the nearby Hotel St. George, informing them that, for $1, they could enjoy a “healthful” swim (“sun and suits” included). Think of this edition as a cross between a hotel ashtray and a Gideon bible. Telltale stains suggest that this particular Austen copy doubled as a coaster. In addition, it was re-gifted because it is inscribed “From Dave to Zelma” on the inside cover, complete with a December 1931 date. In the Hotel Taft series, Jane Austen kept company with the likes of Arthur Conan Doyle and Kipling. All three authors were bound in the same orange and black cover design, as if dressed in hotel livery. |

|

|

|

|

Jane Austen as the perennial birthday and Christmas gift Birthday and Christmas wishes are ubiquitous in old Austen copies, especially in popular editions marketed to young readers. Because long-running series like this Ruby edition of Mansfield Park (circa 1910) and this Dean’s Classic edition of Pride and Prejudice (circa 1960) remain undated on their title pages (this kept a publisher’s stock looking fresh for years) and often go unrecorded by bibliographers, gift inscriptions can be a huge help in narrowing down publication dates. Across the fly leaf, this copy of Mansfield Park is inscribed with a fountain pen in a flowing hand: “To Marjorie:—With much love and best wishes. From E. A. Wayne. Feb 13/1910.” Half a century later, it is a blue ballpoint pen that neatly inscribes this abridged edition of Pride and Prejudice: “Peter Homes. Bedingham. Christmas December 25 1962. With every good wish. From P. H. Yackman. Bedingham. December 25 1962.” The names of the books’ recipients confirm that, as late as 1962, Austen was considered fit food for young gallants as well as ladies. |

|

Cheap gift books like those shown above often fail to secure mention in bibliographies. As a result, such popular editions have not, for the most part, been collected by rare book libraries. Having judged the central text of these rough versions as unauthoritative and inaccurate, scholarship has traditionally dismissed this whole category of gift book as unworthy of critical notice. Yet, when the splendid ordinariness of many popular editions are gathered together, even giveaways, school certificates, and inscriptions can help establish a fuller record of the reception history of Jane Austen.

Meanwhile, happy birthday, Jane! Congratulations. After two centuries, you are still gifted.

Janine Barchas is the author of Matters of Fact in Jane Austen: History, Location, and Celebrity. A professor of English at the University of Texas, Austin, Barchas is the creator of the What Jane Saw website at http://www.whatjanesaw.org. Read her New York Times Book Review essay on the packaging of Jane Austen over two centuries.