Guest post by Ralph Eshelman and Burt Kummerow

On June 14, 1777, the Continental Congress approved the design of a national flag. Since 1916, when President Woodrow Wilson issued a presidential proclamation establishing a national Flag Day on June 14, Americans have commemorated the adoption of the Stars and Stripes by celebrating June 14 as Flag Day. To encourage a better appreciation of the story behind the Star-Spangled Banner, we offer an edited excerpt from our book, In Full Glory Reflected: Discovering the War of 1812 in the Chesapeake.

A Flag and a Song

“Then, in that hour of deliverance, and joyful triumph, the heart spoke; and, Does not such a country, and such defenders of their country, deserve a song?”—Francis Scott Key, 1836

It all began with an arrest. Sixty-five-year-old Dr. William Beanes (1749-1828) of Upper Marlboro was a respected physician and Revolutionary War veteran well known in the Washington region. He had cordially entertained both General Robert Ross and Admiral George Cockburn when the British Army marched through on its way to attack Washington.

The trouble began when the British were returning to their ships. Enemy stragglers were looting in the neighborhood and Dr. Beanes helped local citizens arrest the troublemakers. The British brass was not amused. Dr. Beanes, arrested in his bed, soon found himself and two companions in irons on board a Royal Naval ship. The next stop might be Halifax, Nova Scotia, or, even worse, England’s Dartmoor Prison.

The trouble began when the British were returning to their ships. Enemy stragglers were looting in the neighborhood and Dr. Beanes helped local citizens arrest the troublemakers. The British brass was not amused. Dr. Beanes, arrested in his bed, soon found himself and two companions in irons on board a Royal Naval ship. The next stop might be Halifax, Nova Scotia, or, even worse, England’s Dartmoor Prison.

Richard West, a close friend of the doctor, approached his brother-in-law, the influential 35-year-old Georgetown lawyer Francis Scott Key (1779–1843), for assistance. He was well-connected in the Federal City. Key met with President Madison who then met with General John Mason, the commissary general of prisoners. They approved a mission to seek the release of Beanes and requested that Key accompany American Prisoner Exchange Agent John Stuart Skinner. In Baltimore they boarded a flag of truce packet ship and sailed south to the British fleet near the mouth of the Potomac River. Boarding Admiral Cochrane’s flagship, HM Ship-of-the-Line Tonnant, the party was greeted coldly by the senior British officers when the purpose of their mission was revealed. At first General Ross was unwilling to release the doctor. However, when letters from wounded Englishmen were shown lauding Beane’s medical treatment, the General and his naval colleagues agreed to let the doctor go. They also detained the truce party so as not to allow them to report about the British plans to attack Baltimore. Before the battle, Key, Skinner, and Dr. Beanes were returned to their truce boat still under guard. There, they unwittingly found themselves at the very center of the Battle for Baltimore.

Mary Pickergill, along with many helpers, hand sewed the new garrison flag for Fort McHenry in 1813.

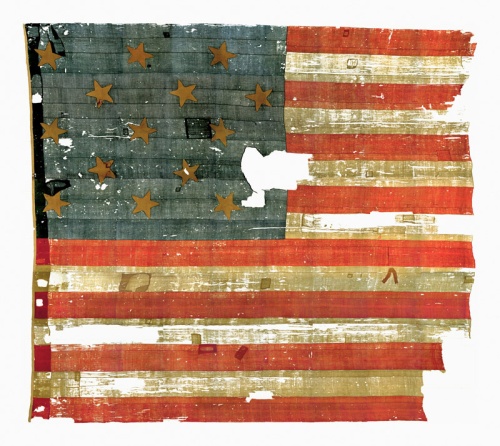

If not during the bombardment of Fort McHenry, all three gentlemen undoubtedly saw the flag flying over the fort when they entered Baltimore harbor two days after the British fleet withdrew down the Patapsco, having failed to take the fort or the city. The garrison flag (30’ x 42’) was commissioned by the fort’s commander, Major George Amristead, along with a smaller storm flag (17’ x’25’) the year before. The flagmaker, Mary Pickersgill, a thirty-seven-year-old widow, was an experienced ship and signal flag maker. She labored on the garrison flag for seven weeks with her 13-year-old daughter Caroline, two nieces (13-year-old Eliza Young and 15-year-old Margaret Young), a 13-year-old African American indentured servant, Grace Wisher, and possibly her old mother, Rebecca Young, who had taught her the trade. They pieced together strips of loosely woven English wool bunting, then laid the whole flag out on the floor of a brewery near Mrs. Pickersgill’s Pratt Street house.

Key and his colleagues had perhaps the most unique location to observe the bombardment among all Americans, since they had a front row seat among the enemy for the drama that unfolded. At dawn, the men were all straining to see the fort and the flag. The British stopped their bombardment and an eerie quiet settled over the harbor. The three Americans slowly realized the British were retiring. The attack was over.

This is the first published version of the “Star-Spangled Banner” that identified the author but incorrectly refers to Francis Scott Key as “B. Key, Esqr.” Note at the beginning of the song it states “With Spirit.”

In Baltimore, Key spent the evening at the Indian Queen Hotel. It is there that he wrote the four stanzas to a tune that he probably had dancing in his brain on the truce ship. That original manuscript, entitled “The Defence of Fort M’Henry” and written with only a few corrections, is on display today at the Maryland Historical Society.

From the beginning, Key intended for the stanzas to be sung “To Anacreon in Heaven,” an eighteenth-century English club song that was already popular in America. An amateur poet and lyricist, he had been toying before with both the patriotic ideas in the lyric and the tune of the song.

Bands played the song regularly during the Civil War, and the U.S. Navy made it an official part of their flag ceremonies in 1889. President Woodrow Wilson ordered it be played for military ceremonies during World War I. President Herbert Hoover finally signed a law on March 3, 1931, making “The Star Spangled Banner” the official anthem of the United States.

After a decade long, multi-million dollar restoration, the Star-Spangled Banner flag is again on permanent display at the National Museum of American History in the nation’s capital.

Ralph E. Eshelman is a cultural resource consultant, historian, researcher, and writer; he is the author of A Travel Guide to the War of 1812 in the Chesapeake and coauthor of The War of 1812 in the Chesapeake, both published by JHU Press. Burton K. Kummerow is president and CEO of the Maryland Historical Society and president of Historyworks, Inc. Together, they are coauthors of In Full Glory Reflected: Discovering the War of 1812 in the Chesapeake, published by the MdHS Press in collaboration with the Maryland Historical Trust, the National Park Service, and the Maryland War of 1812 Bicentennial Commission. Images from the book used in this blog post appear courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society, the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, and illustrator Gerry Embleton.

Ralph E. Eshelman is a cultural resource consultant, historian, researcher, and writer; he is the author of A Travel Guide to the War of 1812 in the Chesapeake and coauthor of The War of 1812 in the Chesapeake, both published by JHU Press. Burton K. Kummerow is president and CEO of the Maryland Historical Society and president of Historyworks, Inc. Together, they are coauthors of In Full Glory Reflected: Discovering the War of 1812 in the Chesapeake, published by the MdHS Press in collaboration with the Maryland Historical Trust, the National Park Service, and the Maryland War of 1812 Bicentennial Commission. Images from the book used in this blog post appear courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society, the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, and illustrator Gerry Embleton.